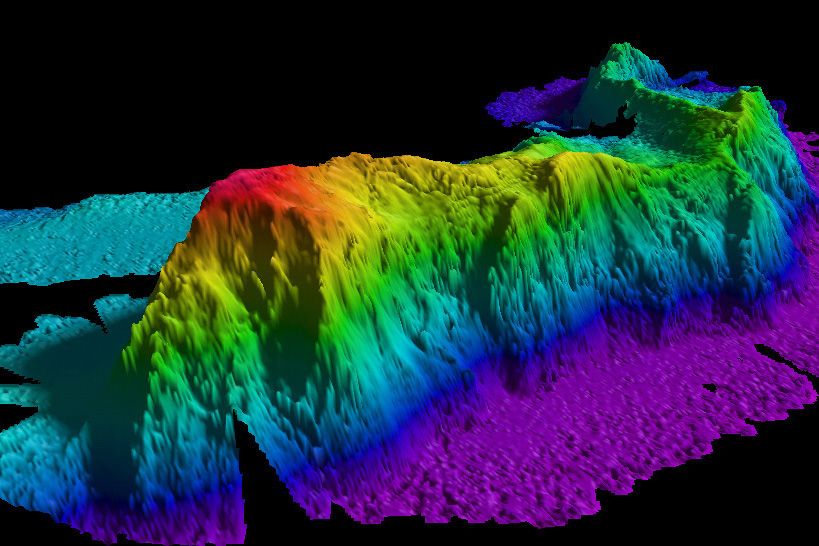

Colossal undersea mountains, rising to thousands of meters high, cause deep sea currents to stir, affecting how our ocean stores heat and carbon. An international team led by the University of Cambridge used numerical modeling to measure the impact of underwater turbulence around these mountains, known as seamounts, on ocean circulation. They found that this turbulence is an important mechanism in ocean mixing, but it’s currently not accounted for in climate models used for policymaking.

Deep-sea turbulence around seamounts has been measured before, but its significance in ocean circulation on a global scale was uncertain. According to the research team, the stirring around seamounts contributes to around one-third of ocean mixing internationally. In the Pacific Ocean, where seamounts are more prevalent, this contribution is even higher, at around 40%.

The Pacific Ocean is the largest reservoir of heat and carbon. It’s generally believed that deep water in the Pacific takes thousands of years to resurface. However, if seamounts enhance mixing, especially in large carbon reservoirs like the Pacific, the storage timescale could be shorter. If carbon is released earlier, this could accelerate climate change. Co-author Dr. Laura Cimoli from Cambridge’s Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics highlighted this potential impact.