Concerns have been raised regarding access to the UK Biobank data following claims from “race scientists” that they may have obtained this information. A senior scientist has emphasized the importance of the UK Biobank leadership carefully adhering to established procedures for accessing this data to maintain public trust.

The UK Biobank contains genetic data and medical records from over 500,000 participants, which it shares in anonymized form with researchers to facilitate scientific discoveries and medical advancements. Last week, the Guardian reported that a group called the Human Diversity Foundation (HDF), known for conducting pseudoscientific research asserting fundamental racial differences, was covertly filmed discussing UK Biobank data.

Mainstream geneticists widely regard this type of research as racist pseudoscience lacking credible evidence. The footage was obtained by an undercover activist from the anti-racism group Hope Not Hate and shared with journalists.

In response to the Guardian’s publication, the UK Biobank issued a statement criticizing the report and refuting its findings, asserting that a thorough investigation revealed no evidence of data misuse. The organization indicated that the group was likely discussing publicly available statistics rather than the anonymized data of participants.

However, in correspondence with a senior medical professional the following day, which the Guardian has reviewed, UK Biobank CEO Prof. Sir Rory Collins indicated that inquiries were ongoing. He stated, “Out of an abundance of caution, we are pursuing further investigations to confirm whether any misuse of UK Biobank data has occurred. If we discover that participant-level data have been obtained improperly or that unauthorized analyses have been conducted, we will implement all available sanctions, including legal measures.”

These remarks appear to contradict the Biobank’s public announcement regarding the conclusion of its investigation. When asked about this inconsistency, a spokesperson clarified, “There is no contradiction between our statements. We conducted a comprehensive investigation, including a third-party search of the internet and dark web, and found no evidence of these data being accessible to unauthorized researchers. However, if new information emerges, we will investigate further.”

Biobank’s initial conclusions were partly based on an analysis of a portion of the transcript from the undercover footage released by the Guardian. The organization noted that certain technical details in the transcript raised doubts about the claim that participant-level data—accessible only to approved researchers—had been obtained.

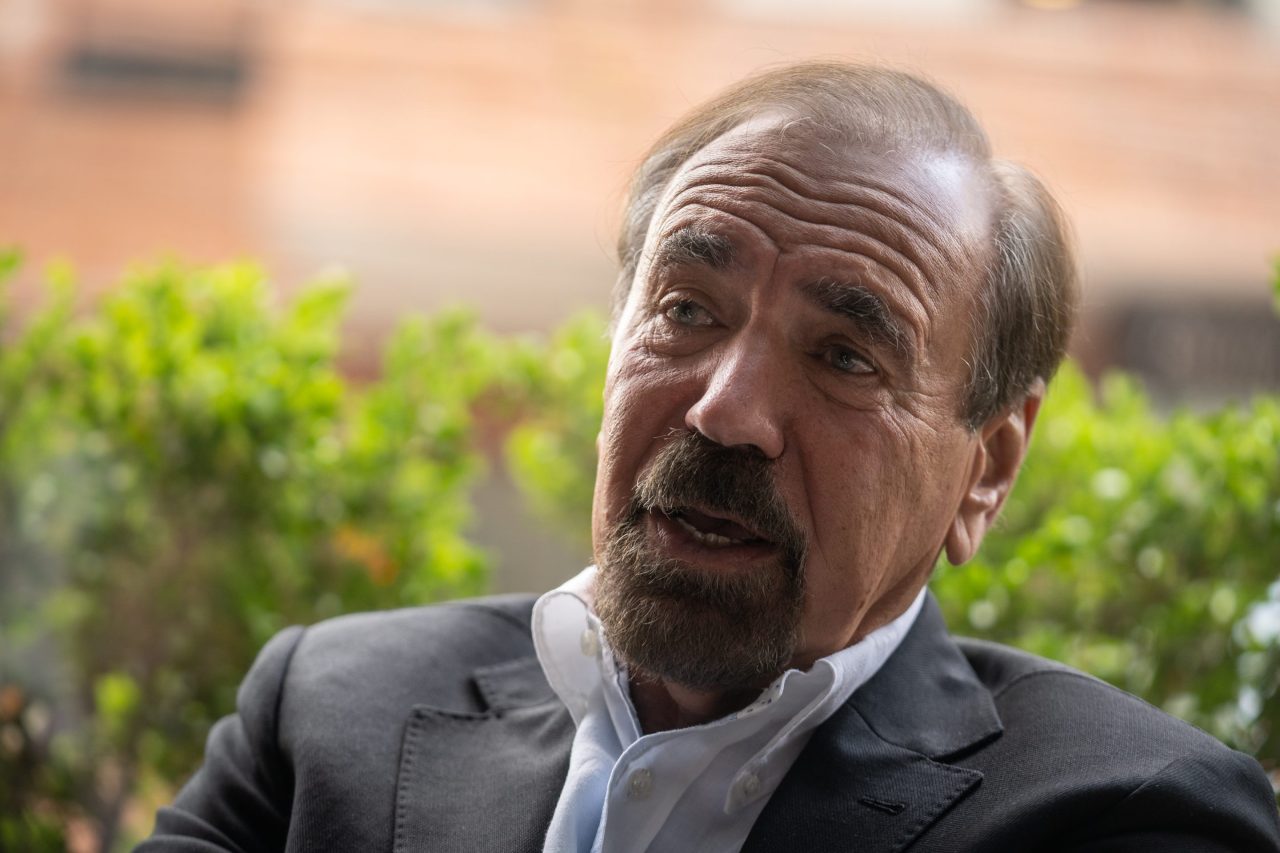

Nevertheless, two senior geneticists and two health data experts who reviewed the same transcript indicated that terminology used by HDF researchers could suggest they accessed such sensitive data. David Curtis, a professor of genetics, evolution, and environment at University College London, cautioned that any implication of the group accessing sensitive genetic data could undermine public trust not only in Biobank but in science as a whole. He questioned whether Biobank had acted too hastily in dismissing the concerns.

“An appropriate response might have been to acknowledge the seriousness of the allegations and to indicate that we are investigating, or that we have requested an external review,” he stated. “Merely asserting that our data scientist has reviewed the situation and found everything satisfactory is insufficient.”

Separately, the Hope Not Hate investigation also captured representatives from a US startup, Heliospect Genomics, describing UK Biobank data as a “godsend” that has enabled them to develop a system for predicting traits such as IQ, sex, height, and risks for obesity or mental illness in human embryos. The company has reportedly assisted couples in testing their embryos as part of IVF treatment and has worked with over a dozen families, according to the undercover footage. Experts have raised significant moral and medical questions about such practices.

Biobank’s stance on Heliospect’s use of its data has evolved throughout the Guardian’s inquiries, leading to some confusion regarding its access policies. Spokespeople stated that Heliospect did not disclose its intention to screen embryos for IQ as part of its commercial application. “All researchers, whether academic or commercial, applying to UK Biobank are required to specify the purpose of their research in their access applications and subsequent annual reports,” the spokesperson noted.

However, the following day, after receiving new information from Heliospect, Biobank revised its statement. “Heliospect confirmed that its analyses of our data have been used solely for their approved purpose of generating genetic risk scores for specific conditions and characteristics, and they are exploring the use of their findings for pre-implantation screening in compliance with relevant regulations in the US,” it stated.

Heliospect indicated to the Guardian that Biobank does not require companies to disclose the exact commercial applications of their research. Curtis raised concerns about Biobank’s approach, arguing for a more rigorous approval process. Dr. Francesca Forzano, chair of the European Society of Human Genetics policy and ethics committee, called for stronger security measures regarding such datasets, stating, “We urge those who manage genomic datasets to ensure that access procedures are governed by robust and transparent protocols, including clarity on how decisions are made regarding the public interest of proposed research. Secondary use of data should be strictly prohibited, and datasets should only be used for their originally approved purposes.”